Site History

The Parish Plan of 1828 shows Hopping Lane (now St Pauls Road) as quite narrow with a line of trees on the South (Marquis Estates) side. This tree line is perpetuated by the limes and sycamores and chestnut of the churchyard today.

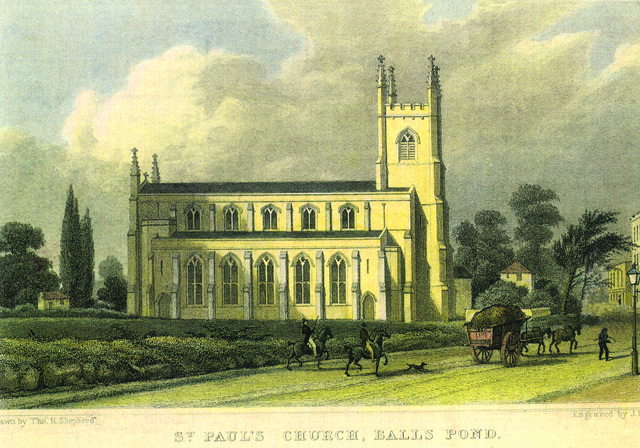

The planning of the site caused some difficulty. The commissioners, whilst intent on economy, wanted some kind of prominence to the church in order to define its position in what would otherwise be a somewhat non-descript road junction. The principal entrance at the west end was therefore given a wide path from St Pauls Road and an expensive west window. The tower was then used as a landmark from the east along Dorset Street opposite. The entrance to the church, although the grandest visually, actually led only up to the galleries.

St Paul's was one of the churches built after the Industrial Revolution to cope with the expansion of London's population and to provide for their educational and administrative needs.

The industrialisation that took place in England in the early 19th century heralded social and cultural changes. One of these was the declining role and influence of the established church. Industrialisation brought about a shift in population from rural to new urban areas. This was not accompanied by an increase in church building. There was one parish church in Sheffield, for example, which in 1615 served a population of 2,207. In 1736 there was still only the one parish church, which now had to cater for a population of 9,965. By 1821, the town's population had grown to 65,275 but by this date only two further churches had been built.

The post-medieval village or town had been dominated by its church - both physically and symbolically; usually built on a commanding position within the parish where it symbolised the authority of the established church.

The parochial system normally served small village communities of 'lowland' rural England. The system broke down in the new urban areas that grew within old parish boundaries. As industrialisation continued at a rapid pace in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, the concentration of population accelerated in the industrial towns.

Where the Church of England responded only slowly to the change and growth of population, other churches and movements grew to fulfil spiritual needs. Growing toleration allowed non-conformist churches to expand outside London, in Islington for example, and to take advantage of the new socio-economic climate. Within those 90 years the Church had lost a monopoly of English religious practice and became a minority religious establishment. The situation had been compounded during the years of economic depression following Waterloo - an age of widespread disturbance, threatened revolution and distress in England, with extensive poverty in both the countryside and towns.

The Church of England slowly realised the need for a massive programme of church building. In the wake of Waterloo, a movement was founded to lobby for the building of new churches to commemorate victory. Late in 1815 it was calculated that in the 50 parishes in or near London, there were not enough Anglican places of worship to accommodate even one tenth of the higher classes in society. The parish system represented the only framework for local civil administration. It was realised that it could not be undertaken by private subscription alone, but only by parliamentary legislation.

The movement gathered momentum over the next two years and a limited programme of church building was outlined in the Prince Regent's speech at the beginning of 1818. On 6th February, at a public meeting chaired by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Church Building Society was launched following a motion proposed by the Duke of Northumberland. A 36-member committee was appointed which included eight future Church Building Commissioners.

The newly formed Church Building Society promptly lobbied parliament for a more far-reaching church building programme than that which had been included in the Prince Regent's speech. The Church Building Society's efforts were successful and parliament passed the first Church Building Act later that year, voting £1 million for the construction of new churches.

The passing of the Act opened a new chapter in the history of church building in England, which MH Port in his book Six Hundred New Churches, describes as one of the four major church-building episodes since the close of the Middle Ages. The Act became popularly referred to as the Million Act, and the churches built under it were known as 'Waterloo', 'commissioners'' or 'million' churches.

It was initially thought that the 1 million would build 100 new churches, and with the aid of subscriptions a further 50 or even 100 additional churches could be built. Populous parishes of at least 4,000 inhabitants were targeted where the existing parish had accommodation for fewer than 1,000 worshippers.